UNITED IN ANGER: A HISTORY OF ACT UP STUDY GUIDE

UNIT 4: DISCUSSION GUIDE

Discussion Section 1: Drugs into Bodies: ACT UP and the FDA

Through grassroots self-education, ACT UP members not only learned the science of HIV/AIDS but also how to navigate the health care system, including federal agencies responsible for the public health. The FDA came under particular scrutiny from ACT UP, whose early call for “Drugs into Bodies” relied on the FDA’s role in making potentially life-saving drugs and therapies available. As early as 1987 the first “FDA 101” presentation was made to the Floor of ACT UP in preparation for informed confrontations with the agency. As United in Anger shows, the combination of scientific and community-based knowledge gave ACT UP a degree of leverage against supposedly faceless institutions, allowing the group to disrupt the status quo of health care bureaucracies, speak back to authority with authority and purpose, and eventually influence new research protocols. Below, we take these issues slowly, one by one, so as to reflect the complexity of the problems ACT UP faced with the FDA.

The Problem: Lack of Access to Experimental Drugs

Because as of 1987 all AIDS drugs except one, AZT, were experimental (they had not completed the FDA standard drug approval process, consisting of three-phase clinical trials) only people enrolled in clinical trials or studies of experimental drugs had access to potentially promising therapies. Without a range of FDA approved drugs, AIDS drug trials effectively became health care.

Yet many people were unable to participate in clinical trials because they were too sick, could not tolerate the drug being tested, lived too far away, or failed to meet the strict criteria for inclusion in the drug trials. Other groups of people were systematically excluded from clinical trials, even though HIV/AIDS was prevalent in their communities. These groups included women, people of color, poor people, people in rural areas, IV drug users, hemophiliacs, prisoners, and children. In the absence of tolerable approved drugs, PWAs needed access to potentially life-saving or –extending experimental treatments before the drugs were approved. ACT UP demanded access to those drugs.

Clip #1

Clip #2

Other problems arose for those who were able to enroll in clinical trials. In certain “double blind” studies, for example, though all participants faced the likelihood of death from AIDS, only some were given the experimental drug being tested. Those in the “control arm” of such studies were given a placebo, essentially a medically ineffectual treatment. Because participants were not informed whether they were given the placebo or the potentially helpful experimental drug, they were unable to make fully informed choices about their own health. Double blind clinical trials were therefore considered by many to be not only unreliable but unethical forms of treatment.

Questions:

1. ACT UP revealed that the scientific and medical communities are not necessarily the neutral entities they claim to be but are, rather, marked by bias and discriminatory ideologies. Why were women, people of color, and many others deemed ineligible for participation in clinical trials? Who became, by default, the “ideal” subject for clinical trials, and what are the ramifications of that inclusion/exclusion process?

Clip #3

2. The American Medical Association defines “informed consent” as a process of communication between a patient and physician that results in the patient’s authorization or agreement to undergo a specific medical intervention. Review the issue of informed consent here. Now discuss the ethical issues that arise when a researcher asks a person who will likely die without medical treatment to consent to the possibility of being given a placebo in a drug trial.

Clip #4

3. ACT UP members proposed what they called “expanded access” to experimental AIDS drugs through a program they developed known as “Parallel Track.” How did Parallel Track respond to the problem of restricted access to experimental AIDS drugs?

Clip #5

ACT UP Solutions:

–“Expanded Access/Parallel Track”: The presentation by ACT UP of its National AIDS Treatment Research Agenda at the Fifth International Conference on AIDS in Montreal, Canada in June of 1989 articulated the first comprehensive plan for AIDS research by anyone and, by demanding full participation of people with AIDS—including previously excluded groups—in the design and execution of drug trials, changed the way AIDS research would be conducted around the world. In that same year, and based largely on the guidelines ACT UP proposed, the FDA and the NIH approved the first Parallel Track program providing wide pre-approval access to a new AIDS drug for people failing AZT.

The Problem: Slow Drug Approval Process and Bureaucratic Red Tape

At the same time that ACT UP was trying to expand access to experimental AIDS drugs, it also focused on the problem of the glacial pace for approval of new drugs. In the late 1980s, the FDA drug approval process for new drugs, a process which required three-phase clinical trials to discover toxicity levels, establish appropriate dosages, prove safety, and show efficacy, typically took between eight and ten years and sometimes longer. But people who contracted HIV often developed AIDS and subsequently suffered and died in a matter of months, while potentially beneficial new drugs were in the approval “pipeline.” ACT UP realized that the FDA needed to respond to the urgency of AIDS deaths by accelerating the regulatory process for AIDS medications or by approving the drugs earlier in the development pipeline. Bureaucratic “red tape,” created by a combination of institutional inefficiency, apathy, and disdain for those affected, proved to be one of the greatest threats to people with AIDS. ACT UP demanded a faster drug approval process.

Questions:

1. Discuss the tension that existed between PWAs, who wanted faster approval of and access to drugs, and the FDA, who was responsible for ensuring that drugs are safe and effective for consumers.

Clip #6

2. What was at stake for people with AIDS? For the FDA?

Clip #7

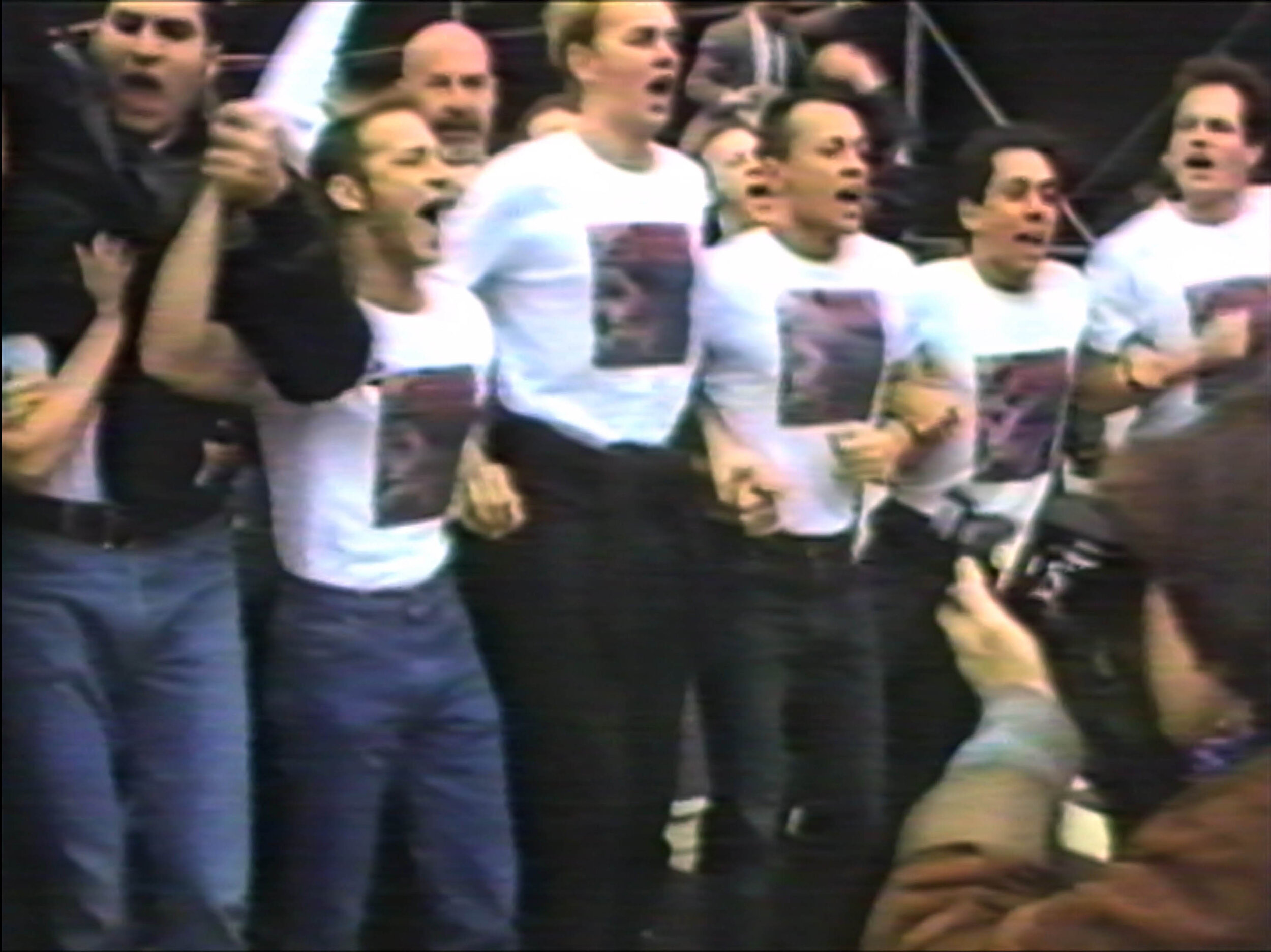

3. What chants, slogans, and tactics did ACT UP use to dramatize the bureaucratic red tape that kept drugs out of bodies? How were these chants and actions rhetorically powerful?

Clip #8

ACT UP Solutions:

–“Accelerated Approval”: In direct response to ACT UP’s concerns, voiced most powerfully at the “Seize Control of the FDA” demonstration in October of 1988, the FDA initiated the accelerated approval process, allowing for expedited access to AIDS drugs. The approval process dropped from eight to ten years to as little as three, with a host of therapies for opportunistic infections available by 1992. Accelerated approval permanently transformed the AIDS crisis, allowing hundreds of thousands of people with AIDS access to medications that extended their lives long enough so that they were able to move on to newer and newer drugs until their health could be stabilized and they could live full or almost full life spans.

Discussion Section 2: Community Experts and the ACT UP Research Agenda

Because of both government and corporate inaction, ACT UP members quickly realized that they needed to become the experts about HIV/AIDS if they were to save their own lives and the lives of others. They became fluent in matters of virology and epidemiology, prevention strategies, treatment options, and caretaking. For example, the Treatment and Data Committee, the primary scientific group within ACT UP, conducted teach-ins about treatment activism. ACT UP also insisted that in many ways people with AIDS were already experts, with valuable knowledge about the ways HIV/AIDS affects individuals and communities. Community expertise produced vital perspectives on and recommendations about more responsive treatment, access to clinical trials, and even the course of AIDS research itself.

The Problem: Scientific Elitism

Scientific and medical advances in the early years of the epidemic were severely limited by a short-sighted national model of who could create knowledge about AIDS. Large government agencies, especially the NIH (and under its auspices NIAID), and well-funded academic research centers were assumed to house “expert” opinion, especially in terms of the capacity to carry out valid scientific inquiry about AIDS. ACT UP, people with AIDS, and individual physicians worked together to intervene in the elite model of knowledge-production, making community-based research standard to the way AIDS science is done.

Clip #9

Questions:

1. What people are typically thought of as medical experts? What kinds of knowledge about HIV/AIDS might a medical expert have that is valuable and necessary? How can a scientist’s prejudices about gay men, women, poor people, people of color, or IV drug users affect their approach to developing treatments?

Clip #10

2. What kinds of knowledge about HIV/AIDS might an HIV+ person or a PWA have that is valuable and necessary?

Clip #11

Clip #12

3. How might a medical “expert”, a pharmaceutical executive, and a person with AIDS have diverging concerns and approaches to HIV/AIDS?

Clip #13

4. Why did ACT UP members need to reconceive of the doctor/patient and researcher/layperson relationship? How did they do it?

Clip #14

Clip #15

ACT UP Solutions:

–A widespread practice in ACT UP, the “Insider/Outsider” strategy was crucial in changing the culture of scientific elitism and advocating for improved medical treatments for people with AIDS. Small groups of deeply informed, often self-taught ACT UP members gained access to the inner workings of institutional science where their scientific knowledge combined with community insight to influence the upper-level decisions about AIDS science. When faced with inflexibility on the “inside” of science, ACT UP would use direct action to apply very public pressure from the outside.

Clip #16

–At the same time, the “insider/outsider” strategy was one of ACT UP’s most controversial approaches because those members who were able to gain access to the inside of the scientific and medical establishment were most often white well-educated males while outside were the masses.

Clip #17

The Problem: Inflexible Clinical Trials and the NIH

If a key demand of ACT UP was to get drugs into bodies faster and more democratically, a second imperative was to improve the actual therapies themselves. This required innovative methodologies for designing clinical trials, as well as for collecting and evaluating their data. Further, because no comprehensive database existed for tracking clinical trials conducted by academic institutions and individual pharmaceutical companies; because trials were often poorly or selectively publicized; and because clinical trial results were often kept secret by drug companies who cited patent infringement concerns, people with AIDS were often unable make informed decisions about how clinical trials might improve their health.

Questions:

1. What is a clinical trial? What is the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG)? Browse the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) website for information about HIV/AIDS clinical trials.

2. Why was it essential for People with AIDS to have input about how clinical trials were conducted? How did their exclusion affect treatment and how did their inclusion change the direction of research?

Clip #18

ACT UP Solutions:

–Community Constituency Group (CCG): One of the most long-lasting structural changes that ACT UP influenced in AIDS research was the addition of the Community Constituency Group (CCG) to the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. For the first time, community members reflecting the diverse constituencies affected by AIDS sat on all ACTG committees of the NIH, including the executive committee, allowing for community expertise and oversight to inform that body. The CCG remains active in all levels of decision making within the ACTG.

Clip #19

–AIDS Treatment Registry (ATR): A spinoff organization from the ACT UP Treatment and Data Committee, the AIDS Treatment Registry (ATR) created a database of all clinical trials testing drugs and therapies for the treatment of AIDS-associated opportunistic infections, allowing people with AIDS to track, monitor, and assess the trials and thus better inform themselves regarding their own health decisions.

The Problem: Profiteering, “Magic Bullets,” and 1996

The earliest—and for years the only—medication approved for AIDS was AZT, a failed cancer drug created in 1964 and whose patent was owned by pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome. AZT has since come to symbolize several underlying problems with AIDS research. Though AZT initially delayed the onset of disease in some patients, the side effects proved unmanageable for many, and because AZT was originally marketed for $10,000 per patient per year (making it the highest profit drug in history) many people with AIDS could not afford it anyway. Further, AZT became the first of several failed “one-pill” or “magic bullet” solutions—an investment of time and resources, as well as hope, in single medications (known as monotherapy) to the exclusion of research into other therapies, therefore impeding the progress of AIDS science. For many years, pharmaceutical companies considered monotherapy to be a preferable path because it created a larger consumer market (a pill for everyone) than combination therapies would. When it was shown in 1993 and ‘94 that AZT—whether taken alone or in combination with other drugs—had little or no positive effect for most people, and in some cases caused patients to die of lymphoma, activists renewed their questioning of the scope of AIDS research, even as ACT UP continued to fracture, made despondent by the continued failure of high-profile drug trials.

Finally in December 1995 the first protease inhibitor, a new class of AIDS drug, was approved by the FDA and quickly integrated into a combination therapy called Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) that relied on three different drugs to suppress HIV. 1996 thus marks a dramatic turning point in AIDS treatment for those with access to the drug “cocktail.”

Questions:

1. What do you know about AZT from the film? Why was it so expensive?

Clip #20

2. Why was the “one pill” solution or monotherapy initially so attractive to scientists, drug companies, and people with AIDS?

Clip #21

3. What were the reactions of ACT UP members in United in Anger to the development of effective AIDS drugs in 1996? Did any of these actions surprise you?

Clip #22

Results:

–Following the “SELL WELLCOME” infiltration by ACT UP at the New York Stock Exchange in September of 1989, pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome lowers the price of AZT—the only FDA approved AIDS drug—by 20% from $10,000 per patient per year (a price which made it the highest profit-making drug in history at the time).

–The ACT UP treatment agenda was designed to develop combination therapies. Shifting focus from a “cure” or one-pill solution that targeted the virus itself, ACT UP pushed for the development of treatments for the opportunistic infections (OIs) that killed people with AIDS. In her ACT UP oral history, Garance Franke-Ruta describes that work:

Clip #23

(Text of full interview with Garance Franke-Ruta)

STUDY GUIDE HOME

UNIT 1: HISTORICIZING ACT UP

UNIT 1: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 2: THE STRUCTURE OF ACT UP

UNIT 2: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 3: ACT UP IN THE STREETS

UNIT 3: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 4: THE POLITICS OF HIV/AIDS MEDICINE

UNIT 4: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES

UNIT 5: ACTIVIST ART

UNIT 5: PROJECTS AND EXERCISES